After decades of politicians promising to get tough on crime, a shift has occurred in the political sphere that could result in reforms.

Prison inmates wearing firefighting boots line up for breakfast at Oak Glen Conservation Fire Camp #35 in Yucaipa, California November 6, 2014. Thousands of convicted felons form the backbone of California's wildfire protection force under a unique and little-known prison labor program. But California may soon find it harder to recruit new inmate firefighters after a ballot measure was passed last month to ease prison crowding by reducing felony sentences to misdemeanor jail terms for most non-violent, low-level offenses, including many drug crimes. That measure will likely diminish the very segment of the inmate population that the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, draws upon to fill its wildland firefighting crews. Picture taken November 6. To match Feature USA-FIREFIGHTERS/CALIFORNIA REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson (UNITED STATES - Tags: CRIME LAW SOCIETY) LUCY NICHOLSON / Reuters

Feb. 24, 2015, 6:21 PM UTC / Updated Feb. 20, 2015, 10:29 PM UTCMusical artists Common and John Legend loudly raised the profile of criminal justice disparities during Sunday's Oscar show. But they aren't the only ones talking about the issue in high-profile ways these days. President Barack Obama will host meetings at the White House on criminal justice reform Tuesday and coalitions from both ends of the political spectrum are coming together both inside and outside of Congress to talk about solutions.

It is one of the few issues that receive any measure of bipartisan support in today's polarizing political environment, but it wasn't always that way. For the end of the 20th century and the first few years of the 21st century, the only acceptable public position to take, especially in politics, was to lock 'em up.

The "tough on crime" era was led by Republicans; Democrats jumped on board in the 1990s; and now Republicans are beginning to abandon the stance as incarceration rates and costs of incarceration reached record highs.

Changing Attitudes

Politicians vowing to be "tough on crime" saw political advantages as early as the turbulent 1960s and lasting throughout the rest of the century.

During the 1980 presidential campaign, President Ronald Reagan vowed to be “tough on crime,” defeating incumbent Jimmy Carter who didn’t campaign on the issue. During the 1988 campaign, George H.W. Bush deployed the infamous Willie Horton ad to depict Democratic challenger Michael Dukakis as being soft on the issue, eviscerating any hope Dukakis had of wining that election. In 1992, Democrat Bill Clinton was aware of the pitfalls of being labeled as anti-public safety so he adopted the Republican playbook.

“We cannot take our country back until we take our neighborhoods back,” the then-Arkansas governor said at a campaign stop at the time.

The repercussions of the bipartisan tough on crime movement included an increase in the death penalty, mandatory minimum sentences, three strikes and you’re out laws, and the war on drugs.

“Democrats became born-again, tough-on-crime fighters,” which made reform more difficult, said Pat Nolan, the former Republican leader of the California Assembly who was sentenced to 2 years in prison for federal racketeering charges in the early 1990s.

Nolan became part of an early group of Republicans committed to reforming the system. While seeing the system from the inside, the conservative lawmaker said, “I had a chance to see the impact of the policies I supported in the legislature,” Nolan said in an interview with NBC News, referring to strict sentencing guidelines and other tough-on-crime measures. “It wasn’t protecting people (from criminals). It was expensive, bureaucratic and wasteful. And we were locking up a lot of people who weren’t dangerous.”

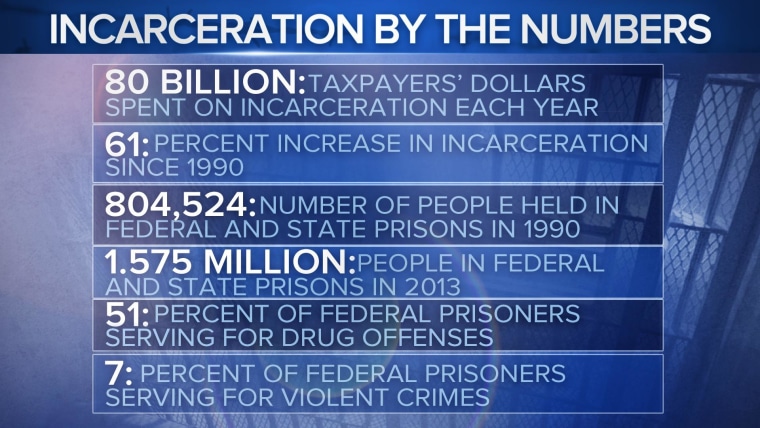

Twenty years later, the U.S. houses more than 1.5 million prisoners in federal and state prisons, more than any other country on a per capita basis and that doesn’t include people local jails and military prisons. But a major shift is happening in the political sphere. Many Democrats have dropped the tough-on-crime persona and some Republicans have as well.

States have begun to reverse many of the tough-on-crime laws that passed, including California which has a major prison overcrowding problem. At the national level, the shift started to take shape in Congress in 2010 when lawmakers dramatically reduced the disparity in sentencing between crack and powder cocaine.

Four years later, some of the most conservative senators, like Ted Cruz of Texas and Rand Paul of Kentucky, are teaming up with some of the most liberal senators, such as Cory Booker of New Jersey and Patrick Leahy of Vermont to address the issue.

In October of 2014, a meeting was convened by philanthropists Laura and John Arnold. Invited were some of the most ideological groups spanning the political spectrum: FreedomWorks and Americans for Tax Reform from the right and the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for American Progress on the left. Out of that meeting the Coalition for Public Safety was formed with participants vowing to present ways to reform various tenets of the criminal justice system.

Charles Koch asked: “If this happens to a big corporation that can afford the best lawyers, what is happening to those who can’t?”

While several foundations are backing the project, including the Arnold Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation and the Ford Foundation, a critical component of this coalition is Koch Industries, a multinational corporation owned by conservative billionaire activists Charles and David Koch that spent nearly a billion dollars to defeat Democrats in recent elections. The Kochs have not placed any limit on how much they will spend on the issue but have already committed a portion of the $5 million donated by the foundations to the coalition.

Like Nolan, the Kochs had their own experience that caused them to question the impact of the criminal justice system.

In the 90s, an oil refinery that belonged to a Koch Industries subsidiary was involved in a court case in Texas over environmental violations. The case turned into a criminal one involving four Koch employees that was eventually settled but after a long, tumultuous process that caused Charles Koch to ask “if this happens to a big corporation that can afford the best lawyers, what is happening to those who can’t?”

After the trial wrapped, the Koch organization started looking into the criminal justice system and determined that the system isn’t working for many.

Now enough conservatives are on board with reforming the criminal justice system that activists are optimistic that things might change.

What changed?

A lot of things.

The cost to taxpayers has become extremely large. Prisons cost $80 billion per year, that’s up to $50,000 per inmate each year in some states. For fiscal conservatives, that’s too a lot of wasted money.

Matt Kibbe, head of FreedomWorks, a conservative group that is committed to small government that is part of the Coalition for Public Safety, said “mass incarceration has ominous fiscal implications, and that matters to a lot of us,” he said.

Kibbe said he briefly touched on the issue in his last book and the FreedomWorks membership, which is active online, responded with veracity, signifying their concern on the issue.

Clinton’s crime bill pumped billions of dollars into states to build new prisons, but Nolan said it didn’t provide any money for operating the prisons.

“Then the bill came due for the guards and the food and the program officers and the equipment and these prisons, which had been a gift from the federal government, began to be a very costly part of the state budget,” Nolan said.

Secondly, the rise of libertarian thought within the Republican Party has spurred harsh critique on the criminal justice system.

Mark Holden, general counsel for Koch Industries said the system is an assault on personal freedom.

“One of the largest intrusive actions by the government is the criminal justice system,” Holden said. “They can take away your life, liberty and property.”

In addition, conservatives began feeling the impact of an overreaching criminal justice system. That’s why Kibbe’s group, FreedomWorks, is intent on reforming civil asset forfeiture, which is when police can take personal property if they believe, without having to prove, it’s connected to illegal activity.

Holden points to the over criminalization of human behavior. He said there are 4500 federal criminal laws that are on the books. “I know I couldn’t list 4500 things that are criminal,” he said.

And Nolan said it’s hard to meet a family who hasn’t been impacted by harsh drug sentencing. “In many of these cases, stupid decisions by young people ended up with dozens of years behind bars,” Nolan said. “That’s not justice.”

Finally, crime rates are at the lowest level that they’ve been in two decades. While numerous studies have shown that an increase in incarceration is not the reason for a reduction in crime, a low crime rate means that it’s not an issue of concern to people.

What sort of reforms?

The list of reforms is long but covers numerous stages of the system, beginning with focusing incarceration on violent criminals and not low level drug offenses. Another is reforming the indigent defense system that often fails people who don’t have money to afford pricey legal representation. At the sentencing stage, eliminating mandatory minimum sentences and disparities in drug laws. Finally, when non-violent criminals have served their time, conservatives are keen on removing the scarlet letter of a felony that keeps them from obtaining school loans, a job or housing.

Impediments

Why many conservatives are hopping on the criminal justice reform train, some aren’t quite there yet, including Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, who is a central figure in any reform moving through the upper chamber because of his role as head of the Judiciary Committee. He has indicated strong resistance to reforming mandatory minimum sentences because drug use leads to criminal activity.