As of 2019, Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D prescription drug plans will no longer be exposed to a coverage gap, sometimes called the “donut hole”, when they fill their brand-name medications. The coverage gap was included in the initial design of the Part D drug benefit in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 in order to reduce the total 10-year cost of the benefit. Subsequent legislative changes are phasing out the coverage gap by modifying the share of total costs paid in the gap by Part D enrollees and plans and requiring drug manufacturers to provide a discount on the price of brand-name drugs in the gap. This data note presents trends on the Part D coverage gap and discusses recent and proposed changes affecting out-of-pocket costs for Part D enrollees who reach the coverage gap.

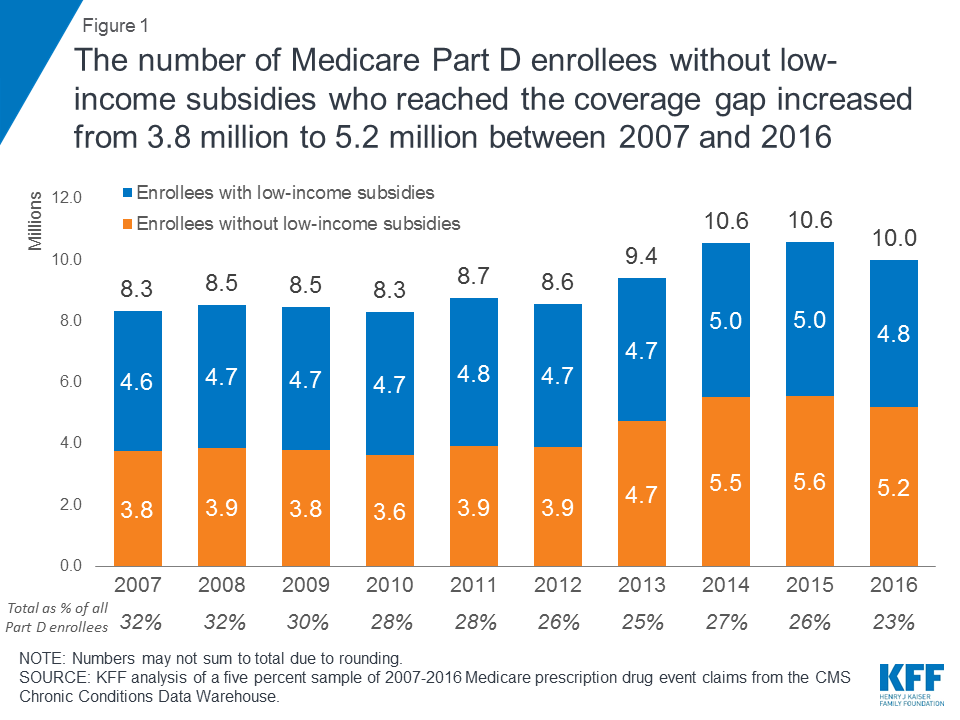

Under the original design of the Medicare Part D benefit, created by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, when Part D enrollees’ total drug spending exceeded the initial coverage limit (ICL), they entered a coverage gap. Enrollees who did not receive low-income subsidies (LIS) were required to pay 100 percent of their drug costs in the coverage gap until their out-of-pocket spending reached the threshold amount that qualified them for catastrophic coverage. (The coverage gap does not apply to beneficiaries who receive low-income subsidies.) In 2007, the first full year of the Part D benefit, 8.3 million Part D enrollees (32 percent of all enrollees) had total drug costs above the initial coverage limit and in the coverage gap (Figure 1). This total includes 3.8 million non-LIS enrollees who were required to pay 100 percent of their drug costs out of pocket in the coverage gap.

Figure 1: The number of Medicare Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies who reached the coverage gap increased from 3.8 million to 5.2 million between 2007 and 2016

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a provision to phase out the coverage gap by gradually reducing the share of total drug costs paid by non-LIS Part D enrollees in the coverage gap, from 100 percent before 2011 to 25 percent in 2020. The ACA required plans to pay a gradually larger share of total drug costs, and also required drug manufacturers to provide a 50 percent discount on the price of brand-name drugs in the coverage gap, beginning in 2011. The ACA stipulated that the value of this discount would count towards a beneficiary’s annual out-of-pocket spending.

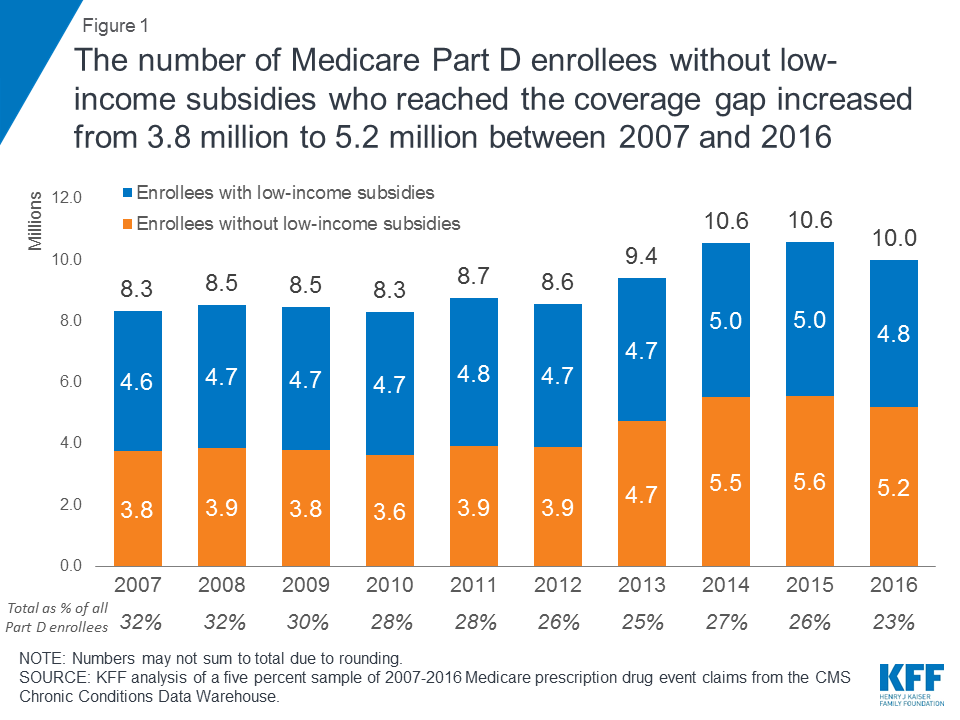

The ACA also modified the calculation of the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold between 2014 and 2019 so that the threshold amount would grow more slowly during these years (Figure 2). In 2020 and beyond, the threshold will be determined using the pre-ACA calculation. As a result, between 2019 and 2020, Medicare’s actuaries project that the out-of-pocket threshold for catastrophic coverage will increase from $5,100 to $6,350, as discussed further below.

Figure 2: The ACA slowed the growth rate for the annual out-of-pocket threshold between 2014 and 2019; in 2020, the threshold is projected to increase by $1,250 in 2020

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA) made additional changes to the coverage gap, accelerating a reduction in beneficiary coinsurance for brands from 30 percent in 2019 to 25 percent that year, and increasing the manufacturer discount from 50 percent to 70 percent, beginning in 2019, a change which is expected to reduce Medicare spending by $11.8 billion over a 10-year (2018-2027) period. In 2019 and later years, Part D plans will cover the remaining 5 percent of costs in the coverage gap, which is a reduction in their share of costs (down from 25 percent that would have been required under the ACA). The manufacturer discount in the coverage gap will continue to count towards beneficiaries’ annual out-of-pocket spending, and will help cover a portion of the projected increase in the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold in 2020 and beyond.

In 2016, the most recent year for which data are available, 5.2 million Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies faced out-of-pocket spending in the coverage gap, an increase from 3.8 million enrollees in 2007, but the number did not rise steadily over these years (Figure 1).

The number of non-LIS enrollees reaching the gap was relatively stable between 2007 and 2012, averaging 3.8 million over these years, even as the overall number of Part D enrollees increased. In part, this is because the amount of total drug spending required to reach the gap (the ICL) increased over these years, based on annual increases in the rate of growth in Part D per capita costs (Figure 2). Between 2012 and 2013, however, the number of non-LIS enrollees reaching the gap increased from 3.8 million to 4.7 million; the fact that the ICL increased only modestly for 2013 could help to account for this one-year increase in enrollees reaching the gap.

In 2014 and 2015, the number of non-LIS Part D enrollees reaching the gap increased further (to 5.5 million and 5.6 million, respectively), before declining to 5.2 million in 2016. The 2013-2014 increase in the number of enrollees reaching the coverage gap is likely due in part to a reduction in the ICL, which resulted from the negative growth rate (-4.0%) used to update Part D benefit parameters for 2014. The 2014-2015 increase may be due in part to the market entry in late 2013 of relatively expensive breakthrough medications to treat hepatitis C.

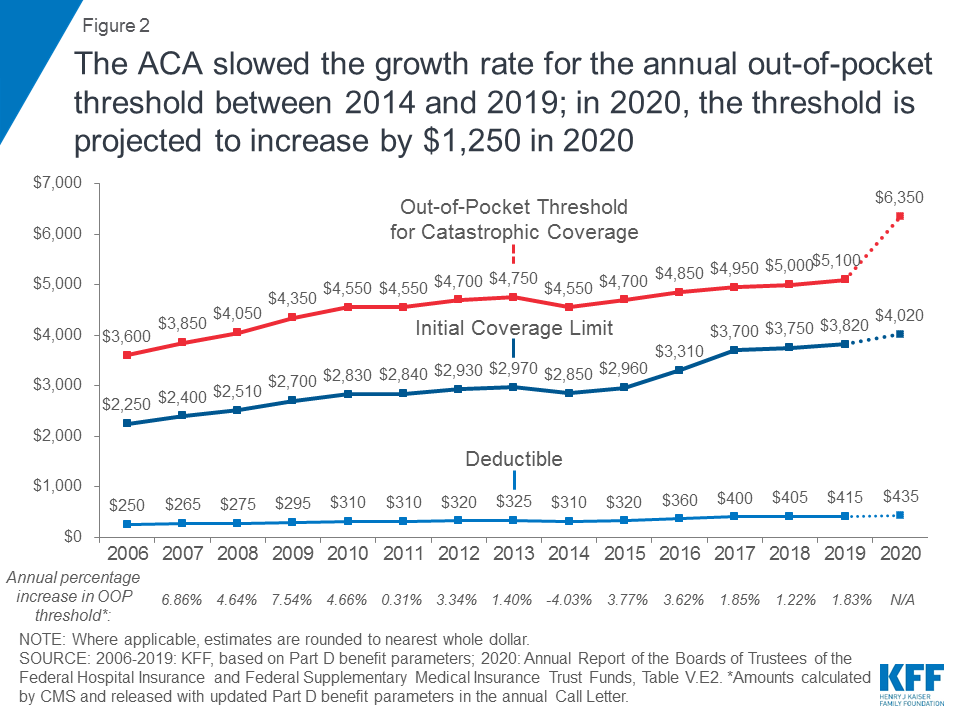

In 2016, average out-of-pocket spending by non-LIS Part D enrollees who reached the coverage gap was $1,569, a decrease from the years before the ACA’s changes to the coverage gap took effect (Figure 3). Between 2010 and 2011, when the 50 percent manufacturer discount took effect and plans began covering 7 percent of total generic drug costs in the gap, average out-of-pocket costs for non-LIS enrollees who reached the gap decreased from $1,858 to $1,485. Between 2011 and 2014, average out-of-pocket costs for non-LIS Part D enrollees who reached the coverage gap decreased by $89, and then increased by $174 between 2014 and 2016.

Figure 3: Average out-of-pocket costs paid directly by non-LIS Part D enrollees who reached the coverage gap decreased when the manufacturer discount took effect in 2011

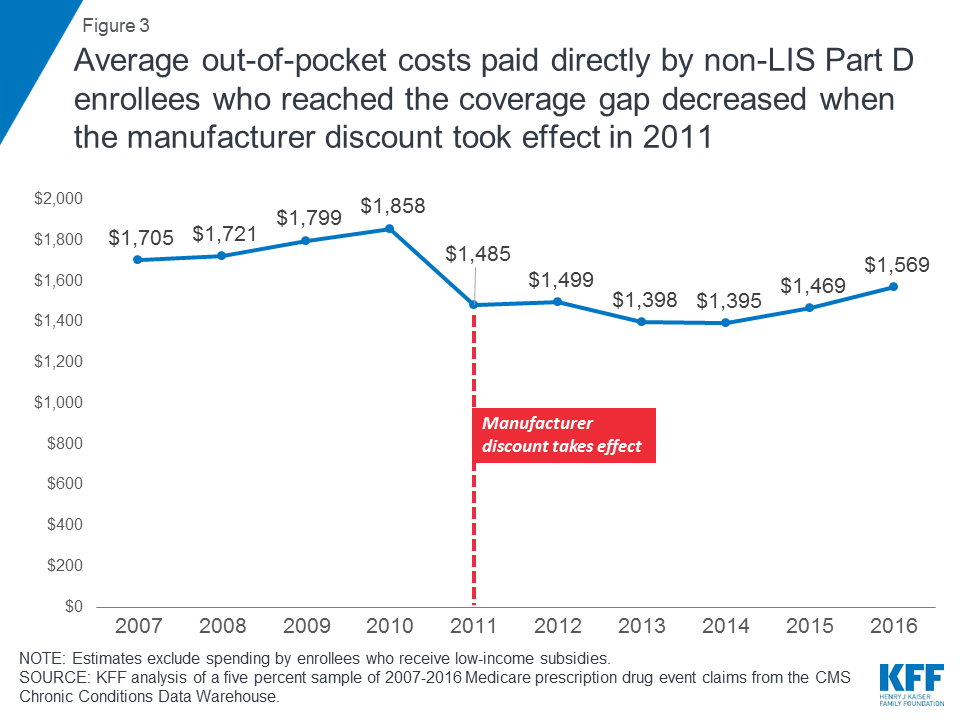

The manufacturer discount on brand-name drugs in the coverage gap represents valuable financial assistance for Part D enrollees with relatively high drug costs. On a per person basis, non-LIS Part D enrollees who reached the coverage gap in 2016 received an average discount on brand-name medications of $1,090, up from $565 in 2011 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The value of the manufacturer discount on brand-name drugs in the Part D coverage gap has increased since 2011, along with the average discount per enrollee

With total Part D drug spending increasing over time and more non-LIS beneficiaries reaching the coverage gap, the aggregate discount that Part D enrollees have received on brand-name drugs has also increased—from $2.2 billion in 2011 to $5.7 billion in 2016.

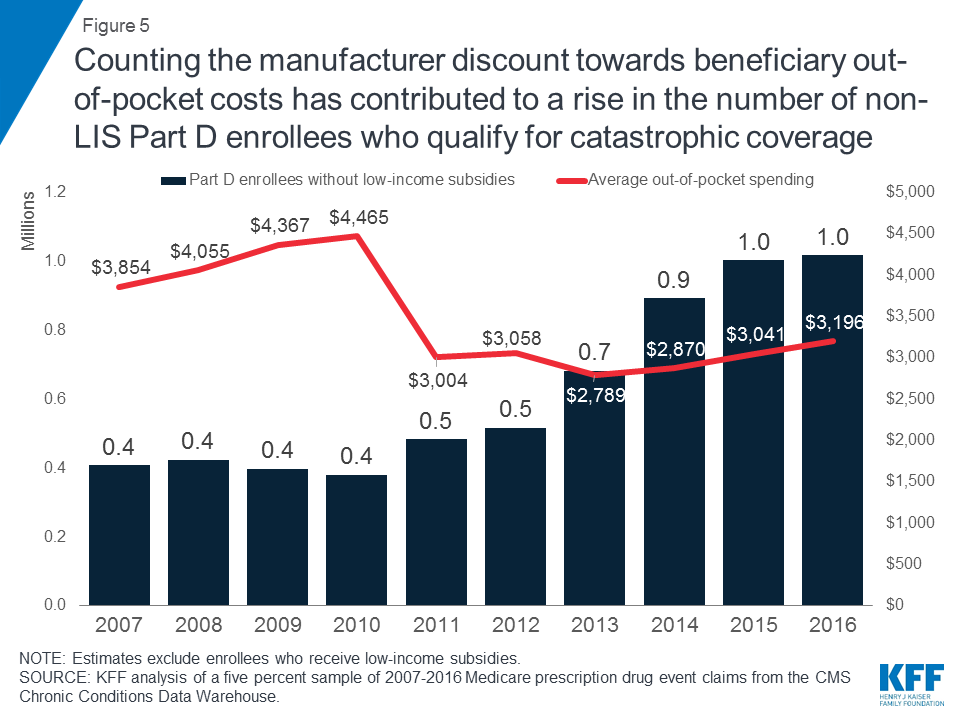

Including the manufacturer discount in the calculation of beneficiary out-of-pocket costs partly explains why more non-LIS Part Denrollees have qualified for catastrophic coverage since 2011 (Figure 5). Non-LIS Part D enrollees move through the coverage gap more quickly because they have to spend less out of their own pockets before qualifying for catastrophic coverage.

Figure 5: Counting the manufacturer discount towards beneficiary out-of-pocket costs has contributed to a rise in the number of non-LIS Part D enrollees who qualify for catastrophic coverage

Between 2011 and 2016, the number of non-LIS Part D enrollees who qualified for catastrophic coverage doubled from 0.5 million to 1.0 million, while their average out-of-pocket costs increased by a relatively modest 6 percent, from $3,004 to $3,196. This trend has contributed to an increase in Medicare Part D spending in recent years, since Medicare pays 80 percent of enrollees’ total drug costs in the catastrophic coverage phase. According to MedPAC, Medicare spending for catastrophic coverage expenses (“reinsurance”) is now the largest, and fastest growing, portion of Part D program spending.

As of 2019, there will no longer be a coverage gap for brand-name drugs, as a result of changes in the BBA. Beneficiary coinsurance for brands in the gap will be 25 percent in 2019, the same share of costs that they face for brands under the standard benefit design before they reach the coverage gap. The coverage gap for generic drugs will not be fully closed until 2020, as scheduled in the ACA. In 2019, beneficiaries will pay 37 percent of the cost of generic drugs, and plans will pay the remaining 63 percent.

Between 2019 and 2020, the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold—the amount of out-of-pocket spending Part D enrollees need to incur to exit the coverage gap and qualify for catastrophic coverage—is scheduled to increase by $1,250, from $5,100 to $6,350. As mentioned above, this substantial one-year increase is due to the expiration of the ACA provision that modified the calculation of the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold between 2014 and 2019; in 2020 and beyond, the threshold will be determined using the pre-ACA calculation.

For Part D enrollees who take mostly brands and who reach the coverage gap, most of this increase in out-of-pocket spending will be covered in the form of the 70 percent manufacturer discount in the gap. For enrollees who take only brand-name drugs, the $1,250 increase would consist of $375 in additional direct out-of-pocket costs, with the remainder in the form of the coverage gap discount.

The Trump Administration has proposed several changes to the Part D benefit, including a proposal to exclude the value of the manufacturer discount from the calculation of enrollees’ annual out-of-pocket costs. (The GOP House Budget proposal for FY2019 included the same provision.) The Congressional Budget Office estimated that this proposal would reduce federal spending by $58.5 billion over 10 years. This change would result in a substantial increase in beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, and would lead to fewer Part D enrollees qualifying for catastrophic coverage, similar to the years between 2007 and 2012. If this change was adopted prior to 2020, the $1,250 increase in the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold scheduled to occur in 2020 would be paid entirely by beneficiaries.

There are efforts underway in Congress to modify the coverage gap changes made by the BBA, while also preventing the upcoming steep increase in the out-of-pocket spending threshold. The effort to modify the BBA changes would reallocate payer liability in the coverage gap, motivated in part by pharmaceutical industry concerns about the requirement that they provide a larger discount on brand-name drugs starting in 2019. In addition, there is some concern that the reduced share of brand-name drug costs paid by plans in the coverage gap will weaken their financial incentive to manage enrollees’ costs once they cross the initial coverage limit and enter the coverage gap phase of the benefit.

Legislation has not yet been introduced to modify the BBA coverage gap provisions, and it unclear whether policymakers are contemplating changes to the beneficiary coinsurance rate in the gap, which is scheduled to be 25 percent for brands beginning in 2019. Increasing plans’ share of costs in the coverage gap and reducing the manufacturer discount to something less than 70 percent for 2019 and beyond would lead to higher Medicare spending relative to current law. Similarly, modifying the scheduled increase in the out-of-pocket spending threshold to protect Part D enrollees from a steep increase in out-of-pocket costs would also result in higher Medicare spending.